Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 06-27-2019

Case Style:

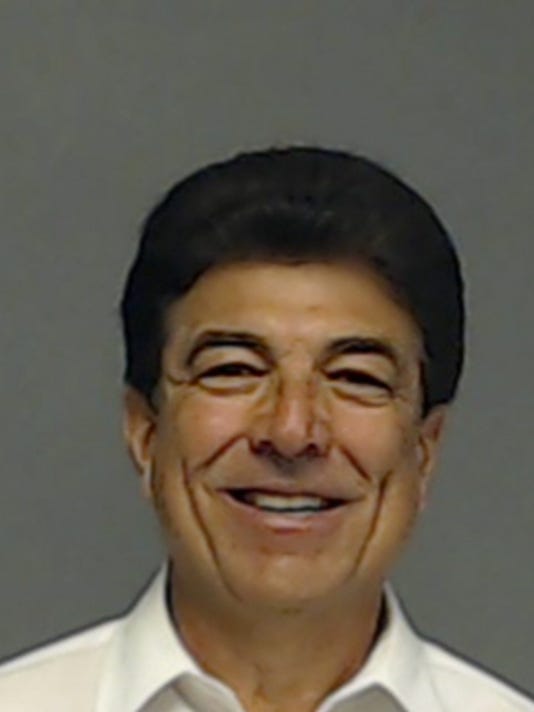

Ray Castro Zapata v. The State of Texas

Case Number: 03-17-00537-CR

Judge: Jeff Rose

Court: TEXAS COURT OF APPEALS, THIRD DISTRICT, AT AUSTIN

Plaintiff's Attorney: Ms. Sarah M. Harp

Mr. Michael Shane Attaway

The Honorable Stacey M. Soule

Defendant's Attorney: Mr. Mark S. Snodgrass

Ms. B. Allison Clayton

Description:

The circumstances surrounding Sullivan’s death and his purported will resulted in a multitude of criminal prosecutions and civil litigation.3 We address the facts relevant to

Zapata’s appeal in some detail, given his challenges to the sufficiency of the evidence supporting

his convictions. Zapata’s assistance with Sullivan’s bail bond and actions after Sullivan’s death Twenty-one witnesses testified during Zapata’s lengthy jury trial. The jury heard

that Sullivan was seventy-seven years old and a resident of San Angelo when he was arrested in

March 2014 for online solicitation of a minor and possession of child pornography. His bond

was set at $1 million for each offense. Sullivan secured his bonds for these offenses with the 2 The facts are summarized from the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial.

3 See, e.g., Chabot v. Estate of Sullivan, No. 03-17-00865-CV, 2019 Tex. App. LEXIS 2145 (Tex. App.—Austin Mar. 20, 2019, no pet. h.); Law Offices of John S. Young, P.C. v. Deadman, No. 03-17-00148-CV, 2017 Tex. App. LEXIS 11230 (Tex. App.—Austin Dec. 5, 2017, no pet.) (mem. op. on reh’g); Young v. State, No. 03-18-00080-CR (pending).

3

assistance of two local bondsmen, Zapata and Armando Martinez.4 Sullivan paid Martinez 15% of the $2 million total bonds ($300,000), and Zapata received $150,000 of that amount.5

Sullivan was released from jail on April 1, 2014. Thereafter, Zapata introduced Sullivan to John

Stacy Young, who became Sullivan’s criminal-defense attorney.

The bailmen considered Sullivan a flight risk. Martinez testified that Sullivan had

a condominium in Spain and the money to do “whatever he wished.” Thus, while Sullivan was

released on bail, Zapata closely monitored Sullivan’s whereabouts. Zapata drove Sullivan to get

food, monitor Sullivan’s real-estate holdings, and collect rent on Sullivan’s properties.

Text messages between Zapata and Young showed that Zapata took Sullivan to a

meeting with Young on June 3, 2014, the day before Sullivan’s body was discovered. After the

meeting, Zapata was unsure whether Young would need to see Sullivan again:

Young: 7:22 a.m. Ray/Need to see john at 930 instead of 915. Can you advise please

Zapata: 7:24 a.m. Yes Sir 9:30

Young: 7:47 a.m. Ray-I’m sorry-945.

. . . .

Zapata: 3:12 p.m. Are you going to want to see John again?

Zapata: 3:13 p.m. So I can tell him and he won’t call everyone… Gracias.

Young: 3:17 p.m. No. We covered it this morning. I’m finishing up with a child porn case-call you later

4 Martinez testified that Zapata did not have the insurance or collateral for $2 million of bonds, so he needed Martinez’s assistance to underwrite them.

5 Martinez testified that Zapata wanted to charge Sullivan 20% of the bond, but Martinez proposed 15% instead because Martinez thought that Zapata’s suggestion of 20% was excessive.

4

Zapata did not testify at trial, but the jury heard evidence6 that Martinez was with

him when they discovered Sullivan’s body on June 4, 2014. Martinez recounted the events of

that day for the jury. Near noon, Zapata called Martinez from outside Sullivan’s house, reporting

that Sullivan did not answer when Zapata knocked on the door to Sullivan’s home and called his

name. Martinez told Zapata that Sullivan might have had someone take him to the senior

citizens’ center and to check the house again after lunch. A few hours later, Zapata called

Martinez to report that Sullivan was still not answering his door. After stopping at the senior

citizens’ center and confirming that Sullivan had not been there that morning, Martinez drove to

meet Zapata at Sullivan’s house. Their knocks at the front door went unanswered, and they

proceeded to the back of the house. Through a window, Martinez saw that all the box fans and

lights were on inside the house. Zapata removed a window screen and a box fan from an open

window, and Martinez climbed inside. Zapata used his phone to photograph Martinez entering

the house, and then followed him in. They split up, searching the house.

Inside the bathroom, Martinez found Sullivan undressed and slumped from the

toilet into the bathtub, dead. Martinez called to Zapata, who came to the bathroom and

photographed Sullivan. Martinez stated that Zapata sent the photo to Sullivan’s criminal-defense

attorney, Young, and called to confirm that Young had received the photo. But Zapata told a

grand jury that he did not send that photo to anyone. While Zapata was speaking with Young,

Martinez told Zapata that they needed to get out of there and call the authorities, but Zapata told

him to wait and give him some time. Shuffling through papers on Sullivan’s desk, Zapata said

6 The jury considered Zapata’s recollection of events in three exhibits admitted into evidence: (1) an excerpt of his testimony during a civil proceeding in probate court on October 7, 2014; (2) the reporter’s record of his testimony before a grand jury on November 12, 2014; and (3) the reporter’s record of his testimony before another grand jury on March 10, 2015.

5

that he had to find a document with “John Sullivan’s signature on it.” Martinez testified that

Zapata eventually let him call 911, and while he did so, Zapata went into the kitchen and

retrieved a book. The book was a missal, a small religious book that looked like a bible. Zapata

took the missal, which he told Martinez that Sullivan had given to him, and placed it in his truck

before the police arrived.

The jury heard an excerpt of Zapata’s testimony at an October 7, 2014 probate

proceeding during which Zapata recalled Sullivan saying that he had “written something here” in

the missal and “if there’s something goes on [sic], it’s right here.” Zapata said that he took the

missal to Sullivan’s attorney with “no idea what was in there.” Additionally, Zapata testified to a

grand jury that when he dropped off the missal to Young at his office, Young’s probate attorney

Christianson O. Hartman was already there, although nobody knew that a will was coming. Emergency application for Sullivan’s cremation and probate proceedings On June 5, 2014, the day after Sullivan’s body was found, Hartman—an attorney

in Sweetwater who had an office building near Young’s—took the missal to the Tom Green

County Clerk’s office and filed it as Sullivan’s holographic will. The alleged will was

handwritten on a page at the back of the missal and dated June 2, 2014. The alleged will listed

Zapata as a witness and named Young, whom Sullivan had known for two months before his

death, as the sole beneficiary. The deputy clerk who handled the filing, Amanda Deanda,

testified that Hartman was “very nervous filing this will.” She also thought it was unusual that

“the will was written on the 2nd of June and [Sullivan] died on the 4th of June, and they filed the

will on the 5th of June.”

On June 10, 2014, Hartman filed an emergency application with the probate court

to cremate Sullivan’s remains. Two days later, Sullivan was cremated. Several witnesses

6

testified at trial that cremation would have been contrary to Sullivan’s particular religious beliefs.

On the same day as Sullivan’s cremation, and before the will was probated giving Young control

of Sullivan’s estate, Zapata sent a text to Young indicating that Sullivan’s house had been

cleared of all papers and that shredding was underway:

Zapata: 9:42 a.m. Buenos Dias. all is well here with Chris and I. Clearing House of all papers is complete. Sorting, Stacking and Shredding is in full swing in Sweetwater.... Do not worry, enjoy weekend and keep the prayers going…. Many Blessings, if you need me just text…. Thanks

Young: 11:40 a.m. You are a good man. I appreciate you more than words express JSY

Also before the will was probated, Sullivan’s longtime attorney Joe Hernandez

saw Young at a criminal-law conference in San Antonio. Hernandez testified that Young asked

him if he had heard that Sullivan, an orphan, had died and left a holographic will witnessed by

Young’s “good friend,” Zapata. Young also mentioned that he had an upcoming hearing before

probate Judge Ben Nolen. Hernandez told Young that Sullivan had a half-sister named Louise

who lived in Worcester, Massachusetts. Hernandez also said that he had contact information for

her and other family members somewhere in his office. Young responded, “Brother, you didn’t

say that. I didn’t hear that.” As Young was backing away, Hernandez chastised him saying,

“John. Come on, John.” Young then said, “You know what Brother, I am going to have to buy

some of your time.” Hernandez understood Young’s remark as a request for an attorney-client

privileged visit with him, so that he would be unable to repeat what Young had just told him.

Judge Ben Nolen testified that during the June 16, 2014 probate hearing in his

court, he placed both Young and Zapata under oath as witnesses. According to Judge Nolen,

Zapata testified as to all things contained in the probate application, including that the will was in

7

Sullivan’s handwriting, that Zapata had witnessed Sullivan signing the will, and that the will was

in the back of a bible that Sullivan owned since childhood. Judge Nolen signed an order on the

same day as the hearing, admitting Sullivan’s holographic will to probate as a muniment of title

and giving all Sullivan’s property to Young. Judge Nolen testified that he would not have

admitted the will to probate if Zapata had testified—as he did later to a grand jury—that he did not witness Sullivan signing the will and that he was unfamiliar with Sullivan’s handwriting.7

Three days after Young received Sullivan’s estate, Zapata requested the payoff amount for a

real-estate loan from his lender, First Financial Bank. Zapata’s financial transactions after probate of will and use of his friend’s IOLTA The jury heard about a series of financial transactions that took place between

Young, Hartman, and Zapata after the alleged will was probated and Young received Sullivan’s

estate. On August 4, 2014, Young wrote a check to Hartman for $167,500. Hartman promptly

deposited Young’s check. On August 9, 2014, Hartman wrote a check for $65,312.50 to Juan A.

Marquez.

Juan A. Marquez testified that he is a Dallas attorney and Zapata’s longtime

friend. Marquez testified that he did not know “Christianson Hartman” or “Chris Hartman.”

Marquez said that Zapata called asking for help, stating that he had a check and that “the lawyer”

advised him not to cash it in San Angelo. Marquez denied knowing that the check was made

payable to him. Marquez offered use of his IOLTA (interest on lawyers’ trust account) at Bank

of America to Zapata. Marquez and Zapata met with a bank officer at a Bank of America

location in Dallas and deposited into Marquez’s IOLTA a $65,312.50 check, made payable to

7 Zapata told a grand jury that the first time he saw the alleged will was the day he testified at this probate hearing.

8

Marquez for “Services & Expense Reimbursement,” signed by Chris Hartman, and drawn from

the Law Office of Christianson O. Hartman, P.C. While at the bank and with Marquez’s

permission, Zapata changed the address for the IOLTA account to his post-office box address in

Christoval, Texas, ordered checks with that new address, and ordered a stamp of Marquez’s

signature.

Bank records admitted into evidence showed that between September 3, 2014,

and January 13, 2015, Zapata and his wife, Julie Zapata, wrote eight checks totaling $60,079.12

from Marquez’s IOLTA using Marquez’s signature stamp. Seven checks were made payable to

Zapata or Zapata Enterprises, and one check paid off a note that Zapata had with First Financial

Bank.

According to Marquez, Zapata later said that “he was having some trouble” and

thinking about giving back the money spent from Marquez’s IOLTA. The evidence showed that

Zapata withdrew $68,000 from his investment account with SWS Group/Southwest Securities on

January 27, 2015, and deposited it into his First Financial Bank account. The next day, Zapata

sent Marquez a check from Zapata’s First Financial Bank account for $60,097.12—the same

amount that Zapata and his wife had spent from the IOLTA. Marquez testified that Zapata sent

him a prepaid envelope and asked him to get a cashier’s check and send it to Hartman’s law

office. Marquez complied, sending a cashier’s check for $65,312.50 to Hartman in early

February 2015, which Hartman promptly deposited. The State contended that this transaction

was an attempt to “reverse” the disbursement of $65,312.50 that Hartman had made to Marquez.

Zapata testified to a grand jury that he had not received any money from Young or Hartman. He

further denied that he had been given or promised anything of value in excess of $2,500 from

any source since Sullivan’s death.

9

Stephen Thompson, who investigates complex financial crimes as a research

specialist with the White Collar Crime and Public Integrity Unit of the Texas Attorney General’s

Office, testified about some of the same financial transactions that Marquez had discussed before

the jury, but in broader scope and greater detail. Thompson described a series of financial

transactions that began shortly after Young received Sullivan’s estate from the probate court on

June 16, 2014. Specifically, on July 25, 2014, Young transferred more than $1 million from an

E*Trade account—originally part of the assets belonging to Sullivan’s estate—to a Sterne Agee

investment account belonging to Young. On August 1, 2014, Young drafted a $235,000 check to

himself from the Sterne Agee account and deposited it into his “Real Estate Account” at First

Bank Texas in Abilene. On August 4, 2014, Young wrote a check from his First Bank Texas

account payable to the Law Office of Christianson Hartman for $167,500. Thompson testified

that Young’s $167,500 check to Hartman would not have cleared without Young’s $235,000

deposit. Evidence showed that as of July 31, 2014, before the $235,000 deposit, the balance in

Young’s First Bank Texas account was only $19,885.58.

Thompson further testified that on August 9, 2014, Hartman wrote a check

payable to Juan A. Marquez for $65,312.50. On August 22, 2014, Hartman’s check was

deposited into Marquez’s IOLTA at Bank of America. Between September 3, 2014, and January

13, 2015, Zapata and his wife Julie wrote eight checks from Marquez’s IOLTA that were

payable to Zapata, Zapata Enterprises, or First Financial Bank, totaling $60,079.12. On January

27, 2015, Zapata withdrew $68,000 from an investment account he and his wife had with SWS

Group/Southwest Securities, and Zapata deposited that $68,000 check into his First Financial

Bank account. The next day, Zapata wrote a check for $60,097.12 from his First Financial Bank

account to Marquez’s IOLTA, but this IOLTA was at Chase Bank, not Bank of America.

10

Marquez subsequently transferred $65,312.50 from his Chase Bank IOLTA to the Law Office of

Christianson Hartman. Authenticity of Sullivan’s will questioned Texas Ranger Nick Hanna testified that Sullivan’s longtime attorney Joe

Hernandez contacted him on June 18, 2014, expressing concern about Sullivan’s will. Ranger

Hanna testified that Sullivan was an educated man, but his purported holographic will contained

several grammatical and spelling errors and at least one factual error. Ranger Hanna also

testified about his investigation, including that on June 4, 2014, after Sullivan’s body was found,

eight phone calls took place between Young and Hartman, fifteen phone calls took place

between Young and Zapata, and seven phone calls took place between Zapata and Hartman. The

calls Zapata had with Young and Hartman that day were deleted from Zapata’s phone. But

Zapata’s phone still had a picture, taken the day before Sullivan’s body was found, of a

delinquent-rent note handwritten by Sullivan and witnessed by Zapata.

Sullivan’s half-sister, Louise Chabot of Worcester, Massachusetts, testified that

she and Sullivan saw each other and communicated intermittently over the years, including a few

visits to each other’s homes and exchanges of letters and Christmas cards. She stated that the

last contact she had with him was in 2000 when their mother died. She recalled that Sullivan

“was from the old school” of his faith and “would never believe in cremation” for himself.

Chabot further recalled that Sullivan typically wrote in cursive, very seldom in print, and often

included something in Latin. She testified that the writing in the alleged will was “not at all” like

Sullivan’s handwriting because it was in print, every letter “I” was in lower case, and the

signature—particularly the way the letter “S” looked like the letter “F”—was not the way that

11

Sullivan typically signed his name. Chabot also noted that the document did not contain any

Latin phrase or religious reference, contrary to Sullivan’s normal practice.

Sullivan’s home-health nurse, Willie Ruiz, testified that he saw Sullivan’s

signature several times a week over the eighteen-month period that he was caring for Sullivan.

Ruiz explained that Sullivan had to sign for every visit that Ruiz made to Sullivan’s house and

that the signature on the will did not look like Sullivan’s because Sullivan’s actual signature

would have been much larger. Ruiz stated that the language used in the will was “too

elementary” and “written at a lower level of intelligence,” not the way that Sullivan would have

written. Ruiz also stated that he was surprised to learn of Sullivan’s cremation because Sullivan

“was very much against it.”

Scott Quinn, a former fundraising director at a school for priests called the

Society of Saint Pius X, had a close relationship with Sullivan. Quinn confirmed that the Society

had not received money, if there were any, from an account at San Angelo Federal Credit Union

that Sullivan had designated as “payable on death” to the Society. Quinn also acknowledged that

Sullivan made large Christmastime gifts to the Society—including a $100,000 check that he

wanted to go to an orphanage in India—and that Sullivan intended to leave a substantial part of

his estate to the Society. Quinn opined that the alleged will did not look like a document that

Sullivan would write because it omitted any Latin phrase, it was not in Sullivan’s “very neat and

beautiful” handwriting, the size of writing was tiny, the words were indicative of an intellectual

ability less than Sullivan’s, and the signature looked nothing like Sullivan’s.

Sarah Pryor, a forensic document examiner in the Questioned Document section

of the Texas Department of Public Safety Crime Lab, testified about her examination of

handwriting from Sullivan, Young, and Zapata. Pryor’s work included comparing the

12

“questioned document,” i.e., Sullivan’s alleged will, with handwriting exemplars8 and

documents written in the normal course of business from Young and Zapata. She stated that

forensic document examiners express their scientific conclusions on a seven-category scale,

ranging from “Elimination”—meaning the person whose handwriting is being compared would

not have written the questioned document—to “Identification”—meaning that the person wrote

the questioned document. The category at the center of the scale, “Inconclusive,” means that

there is no basis for either an identification or elimination. The categories progressing from the

center toward the elimination end of the scale are “Indications May Not Have Written”—

meaning that there is evidence supporting that the person did not write the questioned document,

and “Strong Probability Did Not Write”—meaning that it is a virtual certainty that the person did

not write the questioned document. Similarly, the categories progressing from the center toward

the identification end of the scale are “Indications May Have Written”—meaning that there is

evidence supporting that the person did write the questioned document—and “Strong Probability

Did Write”—meaning that it is a virtual certainty that the person wrote the questioned document.

Pryor acknowledged that in the hundreds of document examinations she has conducted, her

conclusions have not usually been on the extreme ends of the scale.

Pryor testified that her conclusions about the handwriting in the alleged will were

broken into two portions: the “extended portion,” or body, and the signatures (those of Sullivan

as testator and Zapata as witness). In summary, Pryor’s analysis concluded that there were

indications Sullivan might not have written the signature or the extended portion of the alleged

8 Pryor explained that exemplars are samples created by dictating the questioned document to a person and having them handwrite the material verbatim from the questioned document. Here, Ranger Hanna administered the exemplars to Young and Zapata as part of the case investigation.

13

will. Further, after examining several distinctive characteristics of Zapata’s handwriting that

were also present in Sullivan’s alleged will—including loops in the lower case letter “p,” using

the capital letter “R” between lower-case-lettered words; using a capital letter “D” at the end of

lower-case-lettered words; linking the lower-case letters “iv” in a way that appeared to be a “w”;

and crossing pairs of the lower case letter “t” with one crossbar—Pryor concluded that, “[t]here

are indications that Ray Zapata may have written the extended portion” of the will, meaning

“there is evidence to support that he may have been the writer.”

Samuel Allen, a San Angelo attorney who handles some probate work, testified

that he knew Zapata personally and that he spoke with Zapata on behalf of a client on June 11,

2014, less than one week after Sullivan’s body was discovered. Allen asked Zapata whether he

was present when Sullivan signed the will, whether Zapata had witnessed Sullivan’s signature on

the will, and whether Zapata signed the will as a witness. According to Allen, Zapata answered

“yes” to those questions. Allen “sensed that [Zapata] was uncomfortable” after a few questions,

and Zapata referred Allen to the attorney who filed the pleading in probate court, Hartman.

Tracy Manning, a real-estate investor who executed thirty or forty contracts with

Sullivan beginning in 2009, testified that he recognized Sullivan’s handwriting, signature, and

his typical writing style from their past business dealings. Manning recalled that Sullivan wrote

using proper grammar and spelling, and when Sullivan wrote in print rather than cursive, he used

primarily upper-case letters. Manning testified that the handwriting in the alleged will and the

signature on it did not appear to be Sullivan’s.

14

Sullivan’s former attorney Hernandez testified that his twin brother9 brought

Zapata into the bonding business and that the three men shared an office building. Over the

years, Hernandez became familiar with Zapata’s handwriting. Hernandez testified that the

handwriting and signature on the will admitted into evidence did not appear to be Sullivan’s;

rather, the handwriting appeared to be Zapata’s.

Martinez, the co-bondsman with Zapata who discovered Sullivan’s body, testified

that he had doubts about the alleged will and was surprised that it left everything to Young

because Sullivan “didn’t like attorneys. He hated them.” Martinez further testified that he

confronted Zapata about the alleged will, asking, “How did this happen? How could this be?

You know that this can’t be possible, knowing John [Sullivan]’s intentions. . . . Did you and

John Young make a deal to split the estate or what?” Martinez also told Zapata directly, “This is

a forgery. There has been a crime committed here.” Martinez testified that Zapata did not look

him in the eyes when he responded, “Let the authorities handle it.” Jury’s verdict and Zapata’s sentencing Zapata moved for a directed verdict when the State rested and again at the close

of evidence. The district court denied both motions. The jury convicted Zapata on all four

counts as charged: Count One alleged that Zapata committed forgery by making, completing, or

executing a will purporting to be that of John Sullivan, who did not authorize the writing; Count

Two alleged that Zapata also committed forgery by encouraging, aiding, or attempting to aid

another to pass or publish a forged will to Judge Nolen; Count Three alleged that Zapata

committed theft by aiding Young in unlawfully appropriating money or real property in an

amount of $200,000 or more from Sullivan’s estate or heirs; and Count Four alleged that Zapata 9 Hernandez’s twin brother was deceased by the time of trial.

15

committed money laundering by receiving or possessing checks from Marquez’s IOLTA

account, with aggregate proceeds of $20,000 or more but less than $100,000, derived from the

theft of Sullivan’s estate or heirs.

The district court sentenced Zapata in accordance with the jury’s verdict and

ordered him to pay $1.8 million in restitution to Sullivan’s estate through its temporary

administrator, Michael Deadman. The restitution award was made joint and several with any

restitution that might be ordered regarding these facts, if Zapata’s co-defendant(s) were convicted.10 Zapata filed a motion for new trial that was overruled by operation of law. This

appeal followed.

DISCUSSION First issue: Sufficiency of evidence supporting forgery and theft convictions In his first issue, Zapata contends that the evidence is insufficient to support his

convictions for forgery and theft. He also contends that without proof of his involvement in the

will’s forgery: (1) both of his convictions for forgery fail; (2) there is no “unlawful

appropriation” to support his conviction for theft; and (3) there are no “proceeds of criminal activity” to support his conviction for money laundering.11

Applying a legal-sufficiency standard, we consider the evidence in the light most

favorable to the verdict and determine whether “any rational trier of fact could have found the

essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.” Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307,

319 (1979); Nisbett v. State, 552 S.W.3d 244, 262 (Tex. Crim. App. 2018). “Beyond a 10 See n.3.

11 Because Zapata did not brief any issue challenging the sufficiency of the evidence supporting his conviction for money laundering, we do not address it. See Tex. R. App. P. 38.1(i), 47.1.

16

reasonable doubt, however, does not require the State to disprove every conceivable alternative

to a defendant’s guilt.” Ramsey v. State, 473 S.W.3d 805, 809, 811 (Tex. Crim. App. 2015). We

defer to the jury’s resolution of conflicts in the evidence, weighing of the testimony, and drawing

of reasonable inferences from basic facts to ultimate facts. Isassi v. State, 330 S.W.3d 633, 638

(Tex. Crim. App. 2010). We apply the same standard to direct and circumstantial evidence. Id.

Circumstantial evidence is as probative as direct evidence in establishing a

defendant’s guilt, and circumstantial evidence can alone be sufficient to establish guilt. Nisbett,

552 S.W.3d at 262. Each fact need not point directly and independently to the defendant’s guilt

if the cumulative force of all incriminating circumstances is sufficient to support the conviction.

Id.; see Ramsey, 473 S.W.3d at 809, 811 (concluding that defendant’s forgery conviction was

supported by combined and cumulative force of all evidence, including circumstantial evidence,

viewed in light most favorable to jury’s verdict); De La Paz v. State, 279 S.W.3d 336, 350 n.46

(Tex. Crim. App. 2009) (“While it is hypothetically possible that a case of forgery could be

established by direct evidence, such as eyewitness testimony, most cases of forgery rest on

circumstantial evidence.” (quoting Parks v. State, 746 S.W.2d 738, 740 (Tex. Crim. App.

1987))); see also Acosta v. State, 429 S.W.3d 621, 625 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014) (noting that

conviction for money laundering may be based on circumstantial evidence); Ghana v. State, No.

03-04-00024-CR, 2004 Tex. App. LEXIS 6825, at *5 (Tex. App.—Austin July 29, 2004, no pet.)

(mem. op., not designated for publication) (concluding that circumstantial evidence supported

defendant’s theft conviction). Further, the trier of fact may use common sense and apply

common knowledge, observation, and experience gained in ordinary affairs when drawing

inferences from the evidence. Acosta, 429 S.W.3d at 625.

17

1. Forgery A person commits an offense if he forges a writing with intent to defraud or harm

another. Tex. Penal Code § 32.21(b). “Forge,” in relevant part, means “to alter, make, complete,

execute, or authenticate any writing so that it purports to be the act of another who did not

authorize that act.” Id. § 32.21(a)(1)(A)(i). Forgery is a state jail felony if the writing is or

purports to be a will. Id. § 32.21(d). Zapata contends that there is no direct evidence that the

will was fake and that no one who looked at the will indicated the handwriting was his.

However, the jury had evidence providing context for Zapata’s actions after Sullivan’s death, in addition to evidence that Sullivan did not write the alleged will,12 but rather

that Zapata did, including:

• immediately after the discovery of Sullivan’s body, Zapata delayed Martinez’s call to 911 until after Zapata called Young;

• shortly after the discovery of Sullivan’s body, Zapata had fifteen phone calls with Young and seven phone calls with Hartman, but those calls were deleted from Zapata’s phone;

• Zapata testified to a grand jury that he had only one phone call with Young before calling the authorities and that Young did not call him back;

• during one such phone call with Young, Zapata shuffled through papers on Sullivan’s desk and stated that he had to find a document with Sullivan’s signature on it;

• Zapata removed a missal from Sullivan’s house and placed it in his truck before police arrived;

• Zapata testified that he did not get the missal from the house until after the police were there;

• Zapata did not notify police that he took the missal from the house;

• Zapata kept the missal overnight before delivering it to Young; 12 Zapata acknowledges that the jury heard “testimony speak[ing] to whether the will is fake.”

18

• Before the alleged will was probated, Zapata confirmed to Young that “Clearing House of all papers is complete” and that “Shredding is in full swing in Sweetwater”;

• Zapata had a picture on his phone, taken the day before Sullivan’s body was found, of a delinquent-rent note that Zapata had witnessed and Sullivan had handwritten;

• Sullivan was an educated man, but the alleged will inside the missal contained several errors in grammar and spelling;

• Zapata testified to a grand jury that Sullivan did not sign the alleged will;

• Zapata had previously testified to Judge Nolen that Sullivan did sign the alleged will;

• Zapata testified to a grand jury that he would not be able to recognize Sullivan’s handwriting;

• Zapata had previously testified to Judge Nolen that he did recognize Sullivan’s handwriting;

• Zapata testified to a grand jury that he did not recall his testimony to Judge Nolen about seeing Sullivan writing in the back of the missal;

• Zapata also testified to a grand jury that “there could be somebody else that could have written it [the alleged will], but I don’t think it would be John Young”;

• distinctive characteristics of Zapata’s handwriting were present in the alleged will, including: loops in the lower case letter “p,” use of the capital letter “R” between lowercase-lettered words; use of a capital letter “D” at the end of lower-case-lettered words; linking the lower-case letters “iv” in a way that appeared to be a “w”; and crossing pairs of the lower case letter “t” with one crossbar;

• forensic analysis found indications that Zapata may have written the body of the alleged will;

• according to Chabot, Manning, Quinn, and Hernandez, the handwriting and signature on the alleged will did not appear to be Sullivan’s;

• according to Ruiz, the signature on the alleged will did not look like Sullivan’s;

• according to Hernandez, the handwriting and signature appeared to be Zapata’s; and

• when Martinez told Zapata, “This is a forgery. There has been a crime committed here,” Zapata did not deny the accusations but responded, “[L]et the authorities handle it.”

19

Further, during their deliberations, the jury had all the exhibits admitted into evidence, including

the alleged will and numerous handwriting samples from Sullivan and Zapata. We conclude that

the combined and cumulative force of all the evidence at trial, viewed in the light most favorable

to the jury’s conviction, was sufficient to allow a rational jury to find each element of forgery

beyond a reasonable doubt. See Jackson, 443 U.S. at 319; Nisbett, 552 S.W.3d at 262; Ramsey,

473 S.W.3d at 809, 811. 2. Theft Conviction for the offense of theft requires proof of an unlawful appropriation of

property with the intent to deprive the owner of the property. Tex. Penal Code § 31.03(a). An

“appropriation of property is unlawful if it is without the owner’s effective consent.” Id.

§ 31.03(b)(1). Under the relevant statute, theft is a first-degree felony if the value of the property stolen is $200,000 or more. Id. § 31.03(e)(7).13 A will proponent who knowingly submits a will

for probate with the specific intention of stealing an estate from others with the legal right to

inherit commits theft. See McCay v. State, 476 S.W.3d 640, 646-47 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2015,

pet. ref’d).

Here, Zapata was charged with theft “from the Estate of John Sullivan or from

any heirs of John Sullivan, the owner thereof.” See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 21.08 (“When the

property belongs to the estate of a deceased person, the ownership may be alleged to be in the

executor, administrator or heirs of such deceased person, or in any one of such heirs.”); Edwards

v. State, 286 S.W.2d 157, 159 (Tex. Crim. App. 1956) (op. on reh’g) (concluding “under the

peculiar facts in this case, that ownership of the money at the time it was charged to have been

stolen could be alleged in the estate of Mary E. Rose, deceased”). Zapata contends that “even if 13 See n.1.

20

the will was a forgery and even if he had something to do with it,” the evidence failed to

establish that he knowingly took money from an “owner” as defined in the Penal Code. See Tex.

Penal Code § 31.03(a). Because the Penal Code defines an “owner” as “a person” and defines a

“person” as “an individual, corporation, or association,” Zapata claims that neither statutory

definition includes the State or an estate. See id. § 1.07(a)(35) (preface to definition of “owner”),

(38) (defining “person”). Specifically, Zapata contends that his theft conviction depended on

proof that he knew of an “owner” and that he intended to deprive such owner of property. In his

view, without a “person”—not the State and not an estate—to whom ownership reverted on Sullivan’s death, commission of theft from an “owner” was impossible.14

Zapata’s contention overlooks the broad definition of “person” in the Penal Code

with reference to other statutory subsections. “Person” includes an “association,” which in turn

includes a “government or governmental subdivision or agency,” and “government” is defined as

including “the state.” Id. § 1.07(a)(6) (defining “association”), (24) (defining “government”),

(38). Thus, even if Zapata thought that Sullivan’s estate would escheat, commission of theft

from the State as a “person” and “owner” under the Penal Code was possible.

Zapata’s indictment charged him with theft from Sullivan’s estate or heirs. See

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 21.08; Tex. Penal Code § 31.03(a). The Penal Code does not define

“estate” or “heir.” However, the plain meaning of “heir” is “someone who, under the laws of

intestacy, is entitled to receive an intestate decedent’s property.” Black’s Law Dictionary 839

(10th ed. 2014); see Parker v. State, 985 S.W.2d 460, 464 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) (relying on

legal dictionary for plain meaning of “pass” because it is not defined in Penal Code’s general 14 Zapata denied making any effort to find out whether Sullivan had living relatives, despite sharing an office building with Sullivan’s longtime attorney, Hernandez (who knew Zapata since the 1960s and also knew that Sullivan had a half-sister).

21

definitions or within specific forgery statute); see also Tex. Est. Code § 22.015 (defining “heir”

as “a person who is entitled under the statutes of descent and distribution to a part of the estate of

a decedent who dies intestate”). Under Texas law, the estate of a person who dies intestate and

without a surviving spouse or parents passes to the person’s siblings and the siblings’

descendants. Tex. Est. Code § 201.001(e). Here, during her testimony at trial, Chabot

acknowledged that she is Sullivan’s half-sister and heir to his estate. See id.

Further, the definition of “owner” in the Penal Code includes a person with “a

greater right to possession of the property than the actor [defendant].” Tex. Penal Code

§ 1.07(a)(35)(A) (defining “owner”). The district court provided this definition in its instructions

to the jury. A conviction for theft does not require proof that the defendant knew the identity of

the owner. Cf. id. § 31.03(b)(1); see Lawrence v. State, 20 Tex. Ct. App. 536, 540-41 (1886)

(noting that “to constitute theft it is not essential that the thief should know who is the owner of

the property he has stolen” that theft “embraces the idea that the taker knew that it was not his

own, and also that it was done to deprive the true owner of it”). Thus, under either scenario

Zapata suggests, the State and any heir to Sullivan’s estate would be an “owner” because both

would have a greater right to possession of the property described in the indictment than Zapata

did. See Tex. Penal Code § 1.05(a) (dispensing with strict-construction rule and stating that

provisions of Penal Code “shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to

promote justice and effect the objectives of the code”).

As we have discussed, sufficient evidence supported Zapata’s forgery

convictions. Presentation of that forged will as authentic to Judge Nolen resulted in Young’s

receipt of Sullivan’s estate without the effective consent of “the owner thereof,” i.e., “the Estate

of John Sullivan,” “any heirs of John Sullivan,” or Chabot, who testified that she is Sullivan’s

22

half-sister. Considering the evidence admitted at trial in the light most favorable to the jury’s

verdict, we conclude that a rational jury could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that Zapata

committed the charged offense of theft. See Jackson, 443 U.S. at 319; Nisbett, 552 S.W.3d at

262; Ghana, 2004 Tex. App. LEXIS 6825, at *5. We overrule Zapata’s first issue. Second issue: Admission of Zapata’s grand-jury testimony during trial In his second issue, Zapata contends that the district court violated his

constitutional right against self-incrimination by admitting into evidence a transcript of Zapata’s

testimony before a grand jury panel in 2014 without showing on-the-record admonishments

under article 20.17(c) of the Code of Criminal Procedure. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 20.17(c).15 However, because Zapata’s appellate complaint does not comport with his objections

at trial, this issue is not properly preserved for our review. See Tex. R. App. P. 33.1(a); Yazdchi

v. State, 428 S.W.3d 831, 844 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014) (requiring party’s appellate complaint to

comport with objection at trial to preserve error).

During trial, defense counsel objected to the admission of Zapata’s testimony

before the grand jury because Zapata was not provided the warnings in article 38.22 of the Texas

Code of Criminal Procedure. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 38.22. When the State offered the

grand-jury testimony, counsel told the district court that he would make the same objections he

had made immediately before to an excerpt of Zapata’s testimony from an October 7, 2014

probate proceeding; namely, that Zapata’s statement was made without proper warnings, without

any warnings about magistration, and without showing that it was a true and accurate recording.

See id. Neither magistration nor proper recording are addressed in article 20.17(c), but they are

15 The record reflects that Zapata received admonishments under article 20.17(c) before he began testifying to the grand jury in 2015. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 20.17(c).

23

addressed in article 38.22. Compare id. art. 20.17(c), with id. art. 38.22 § 2(a), § 3(a)(1), (3).

Defense counsel further objected that: there were inadequate warnings as to Zapata’s right to

counsel, Zapata was not properly admonished, there was no showing that Zapata’s statement was

recorded properly, Zapata had not voluntarily waived his rights, and specifically, “the predicates

required under 38.2[2] of the Code of Criminal Procedure” were not met. See id. art.

38.22, § 2(a)(3)-(4), (b), § 3(a)(1)-(3). The district court was never given the opportunity to rule

on an objection raising a self-incrimination issue under article 20.17(c). See Tex. R. App. P.

33.1(a). Moreover, because article 38.22 warnings apply only to statements made by an accused

during custodial interrogations, and not grand-jury investigations, the district court would not

have abused its discretion by admitting the 2014 transcript over counsel’s article 38.22 objection.

See Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 444-45 (1966); Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 38.22, §§ 2, 3;

Nix v. State, No. 12-09-00126-CR, 2010 Tex. App. LEXIS 3717, at *14 (Tex. App.—Tyler May

19, 2010, pet. ref’d) (mem. op., not designated for publication) (noting that individuals in

custody have broader rights than grand-jury witnesses); see also Johnson v. State, 490 S.W.3d

895, 908 (Tex. Crim. App. 2016) (concluding that complaints about trial court’s admission of

evidence are reviewed under abuse-of-discretion standard). We overrule Zapata’s second issue. Third issue: Sufficiency of evidence supporting restitution order In his third and final issue, Zapata challenges the district court’s restitution order

because no evidence supported the initial estate valuation of $8,168,284 and because Sullivan’s market assets may have fluctuated in value.16 See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 42.037(b)(1)

16 The restitution order is based on the evidence indicating that $1.7 million was stolen from Sullivan’s estate and an additional $150,000 of attorney’s fees were incurred in finding the estate assets lost to forgery and theft and converting title of property back to the estate, putting the approximate total restitution at the $1.8 million amount that the district court ordered.

24

(providing that “[i]n addition to any fine authorized by law, the court that sentences a defendant

convicted of an offense may order the defendant to make restitution to any victim of the

offense”). We review challenges to restitution orders under an abuse-of-discretion standard.

Campbell v. State, 5 S.W.3d 693, 696 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) (noting that “[a]n abuse of

discretion by the trial court in setting the amount of restitution will implicate due-process

considerations”); Tyler v. State, 137 S.W.3d 261, 266 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2004, no

pet.) (“Challenges to restitution orders are reviewed under an abuse of discretion standard.”);

Urias v. State, 987 S.W.2d 613, 615 (Tex. App.—Austin 1999, no pet.) (“The restitution ordered

by the trial court will not be overturned on appeal absent an abuse of discretion.”). A trial court

does not abuse its discretion unless its decision is outside the zone of reasonable disagreement

and made without reference to any guiding rules and principles. Gonzalez v. State, 117 S.W.3d

831, 839 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003); Montgomery v. State, 810 S.W.2d 372, 380 (Tex. Crim. App.

1990); Tyler, 137 S.W.3d at 266.

Court-ordered restitution is subject to three limitations: (1) it must be only for the

offense for which the defendant is criminally responsible; (2) it must be only for the victim or

victims of the offense for which the defendant is charged; and (3) the amount must be just and

supported by a factual basis within the record. Burt v. State, 445 S.W.3d 752, 758 (Tex. Crim.

App. 2014). Restitution includes the value of the property on the date of the damage, loss, or

destruction, or on the date of sentencing, less the value of any part of the property that is returned

on the date that the property is returned. Miller v. State, 343 S.W.3d 499, 502 (Tex. App.—

Waco 2011, pet. ref’d); see Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 42.037(b)(1). When, as here, the victim

of the offense is deceased, the trial court “shall order the defendant to make restitution to the

victim’s estate.” Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 42.037(d); Tyler, 137 S.W.3d at 266.

25

Testimony from a witness with knowledge about the amount of damage, loss, or

destruction sustained as a result of the defendant’s offense is sufficient to support a restitution

order. See, e.g., Burris v. State, No. 01-14-00900-CR, 2015 Tex. App. LEXIS 5791, at *3 (Tex.

App.—Houston [1st Dist.] June 9, 2015, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication)

(restitution order supported by testimony from accountant, property owner’s son, about losses

from arson); Strange v. State, Nos. 01-09-00926-CR, 01-09-00927-CR, 2011 Tex. App. LEXIS

3241, at *25 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Feb. 24, 2011, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated

for publication) (restitution order supported by testimony from consultant and accountant who

were hired by victim to perform audit and who determined that $470,000 was missing from

victim’s account); Bailey v. State, No. 05-09-00959-CR, 2011 Tex. App. LEXIS 2389, at *6

(Tex. App.—Dallas Apr. 1, 2011, pet. ref’d) (mem. op., not designated for publication)

(restitution order supported by testimony from victim’s mother, who provided estimate of

expenses incurred after robbery); Todd v. State, 911 S.W.2d 807, 811 (Tex. App.—El Paso 1995,

no pet.) (restitution order was supported by testimony from victim’s mother).

Here, Michael Deadman, the temporary administrator of Sullivan’s estate, told the

jury about the amount of money that the estate lost as a result of Zapata’s crimes. Deadman

testified that it was necessary to determine the value of Sullivan’s estate upon the date of death

for reporting to the Internal Revenue Service in an estate-tax return (“706 filing”). Deadman

testified that the total gross value of the estate, as reported to the IRS, was $8,168,284. During

cross-examination, defense counsel asked Deadman one question about the total gross value of

the estate reported to the IRS on the 706 filing, and Deadman explained that such total was the

sum of values for Sullivan’s real property, notes payable to the estate, and cash on hand.

Defense counsel did not ask Deadman for any further detail supporting the gross value of the

26

estate. See Green v. State, 880 S.W.2d 797, 802 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 1994, no pet.)

(concluding that witness’ testimony was “some evidence” supporting restitution order and that

defendant had opportunity to cross-examine witness about basis for testimony on amount of loss

from theft but defendant did not ask such follow-up questions).

Further, the district court admitted without objection State’s Exhibit 70, a

spreadsheet that Deadman prepared with the assistance of the estate accountant, reflecting the

initial estate valuation of $8,168,284, the estate’s debts, and the “unlocated difference.” If

Zapata thought that the calculations in that exhibit—including the initial estate valuation—were

not properly substantiated, he had the burden to object to its admission. See Lopez v. State, No.

05-16-00041-CR, 2016 Tex. App. LEXIS 10998, at *7 (Tex. App.—Dallas Oct. 6, 2016, no pet.)

(mem. op., not designated for publication) (noting that exhibit supporting restitution order was admitted into evidence without objection from defendant).17

Zapata has not shown that “no evidence” supported the initial estate valuation of

$8,168,284 or that the district court’s restitution order was outside the zone of reasonable

disagreement. See Campbell, 5 S.W.3d at 696; Gonzalez, 117 S.W.3d at 839; Tyler, 137 S.W.3d

at 266. Accordingly, we overrule Zapata’s third issue.

Outcome: We affirm the district court’s judgments of conviction and its order of restitution.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: